Source: Iress iGraph

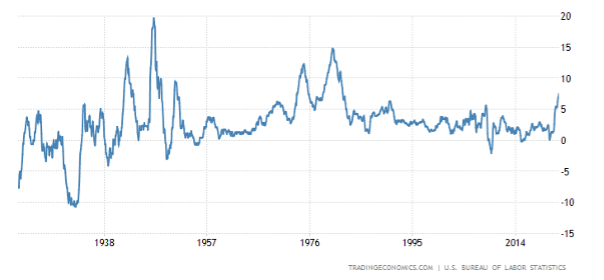

Enter Paul Volcker, nominated in late 1979 by President Jimmy Carter to serve as chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Paul Volcker is widely credited with ending the high rate of inflation and expectations that inflation would continue unabated. US inflation, which peaked at 14.8% in March 1980, fell below 3% by 1983. The Federal Reserve Board, led by Volcker, raised the federal funds rate, which had averaged 11.2% in 1979, to a peak of 20% in June 1981. It is this regime change in monetary policy that caused inflation to decline so significantly (it also caused a recession).

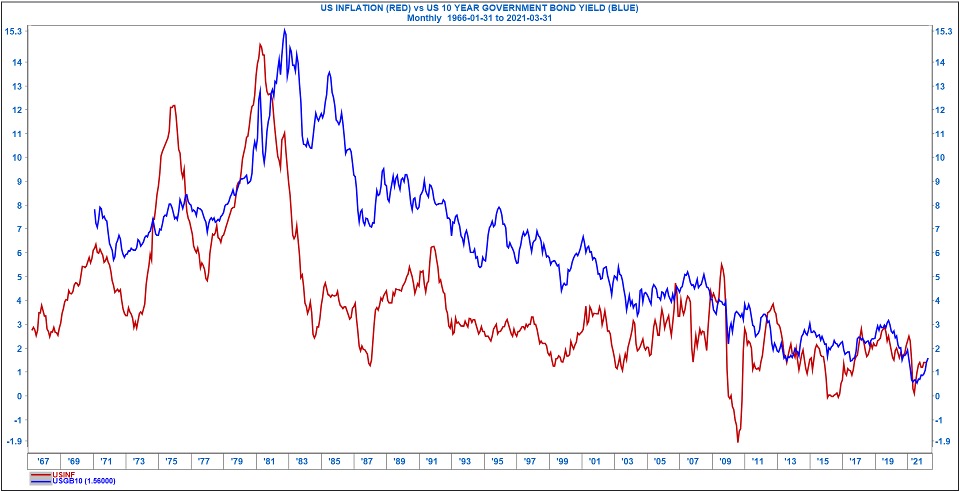

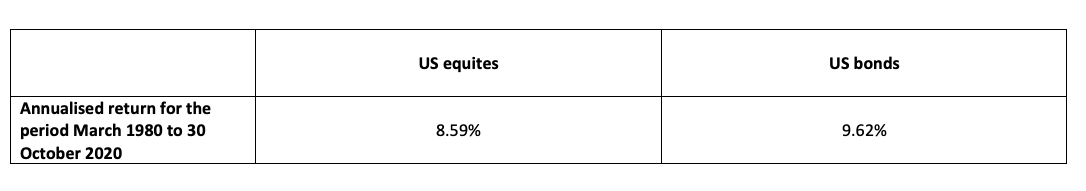

Since then, inflation and interest rates have been in a declining trend. Yes, there have been some other factors at play that contributed. The multi-year process of globalisation, the rise of China as an industrial power and technological adoption all had a deflationary impact. But what was the impact of the Volcker led regime change in monetary policy on the performance of different investments? The table below shows the performance of US equities relative to US bonds from the peak in inflation in 1980 to 30 October 2020. Bond prices are inversely correlated to interest rates and the multi-year decline in inflation and interest rates created strong support for bonds. Quite a tale! Who says equities outperform over the long term? Note, however, that these returns are pre-tax.

Interestingly enough, the evidence in South Africa points to a similar scenario. Inflation peaked in excess of 20% in the 1980’s and when the Reserve Bank governor stepped in and raised the repo rate to around 25%, we saw a massive drop in inflation.

2020

Jerome Powell, the current chair of the Federal Reserve, nominated by President Donald Trump in 2017, might have been leading the US (and the world) into a regime change and possibly a higher inflationary environment. It must be said, the Powell led Fed was, to a degree, strong-armed by President Trump into policy decisions that go against their beliefs. That is an important factor to be aware of, as one could question the independence of the Fed. To what degree do politicians interfere with the Fed and its monetary policy in order to achieve their desires?

Without going into too much detail, I will put forward our thinking at the time. You may have heard of the concepts of Quantitative Easing, Yield Curve Control and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). These are, in effect, recent monetary and fiscal policies that may be used by the Federal Reserve and Treasury to influence interest rates and support economic activity.

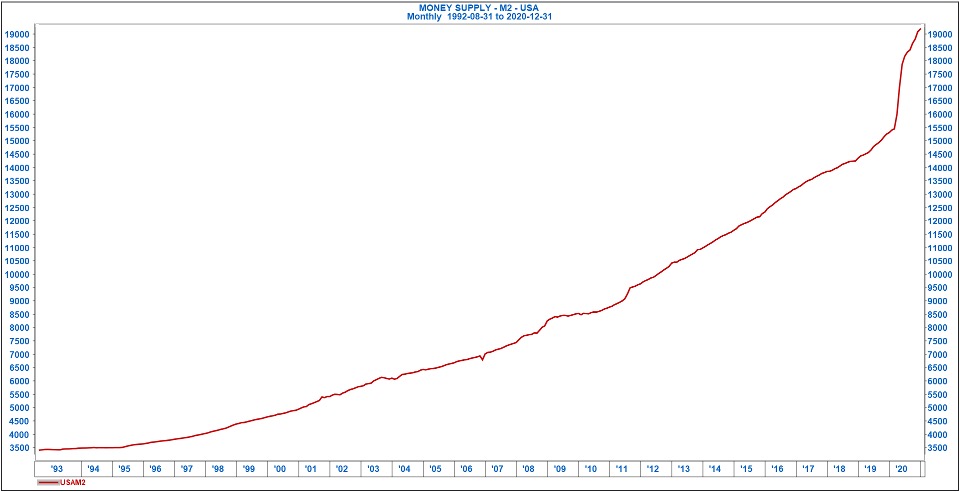

One of the major tools used to stabilise and support the US economy post the 2008 Great Financial Crises was Quantitative Easing, implemented alongside deep cuts in interest rates and various stimulus packages. Quantitative Easing and, more recently, MMT in effect equates to “printing” money. And there was a lot of money printing going on in the US! Cumulatively, over the prior 10 years or so, the Fed injected more than USD 10 trillion into the financial system via various measures! From the March 2020 bottom to the end of October 2020, the Fed injected USD 2.9 trillion into the US economy.

That is certainly a huge amount of money that was put into the financial system. As a result, since the 2008 days of the Global Financial Crisis, market commentators have been arguing for higher inflation. Inflation, however, continued on its downward trend. We started to question why inflation had not reared its ugly head.

One possible answer we came to was that the “printing” of money, or more correctly the Fed’s balance sheet expansion or lending practices, did not translate into money in the hands of households. In short, the Fed created credit or lent money to institutions like banks, not individuals (the Fed does not spend money). They did this by buying securities (bonds) by way of their asset purchase programs.

In other words, the Fed purchased bonds from banks and credited these banks’ accounts with them with an amount of money, say USD 1 billion. All that happened was that the bank’s reserves with the Fed increase by USD 1 billion. Money was created out of nothing. But the banks did not lend this money to consumers as banks lend based on their capital and not their reserves held with the Fed. The money “printed” remained in the banking system.

Quantitative easing, the asset purchase program, balance sheet expansion or money “printing” – call it what you will, did not cause conventional inflation. It caused asset inflation. What these practices caused was a reduction in the stock outstanding of securities like bonds. The increased demand for bonds by the Fed led to price increases in bonds and lower interest rates. The result – a conservative investor may have to buy a longer maturity bond to earn a better yield. A cautious investor may have to consider municipal or high yield bonds and a moderate investor may have to start to look for high yielding equities.

So, as the Fed buys bonds, the available pool of investments may shrink while the pool of money looking for a home stays the same. Voila, asset inflation! Wall street benefits and Main street still struggles. There is no transmission mechanism of the Fed’s balance sheet expansion from the banks to households. And most of the people who own investments are already rich and becoming richer won’t encourage them to spend more on basics.

The Fed does not cause inflation by “printing” money, they are not giving money away and are not spending money either. The government is another story, they can spend money, it’s called fiscal policy, more about that later.

Over the last two decades:

1. The effectiveness of monetary policy has diminished

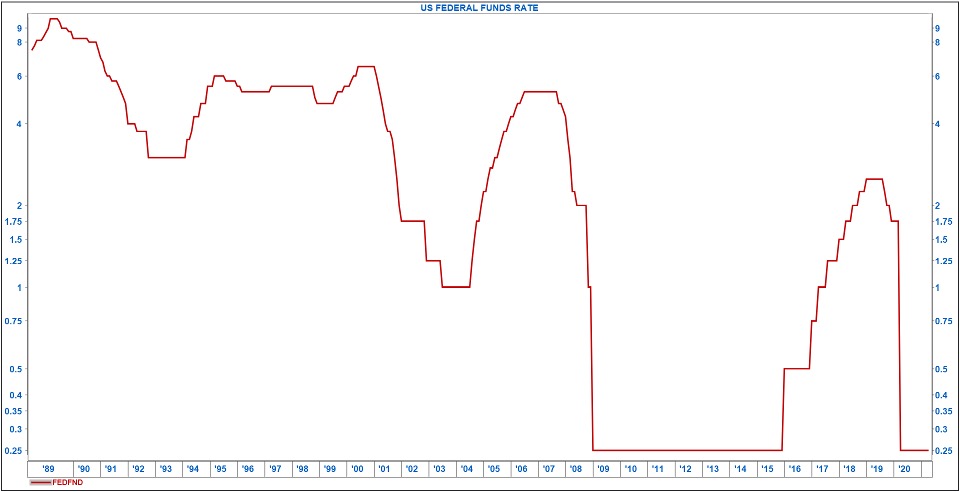

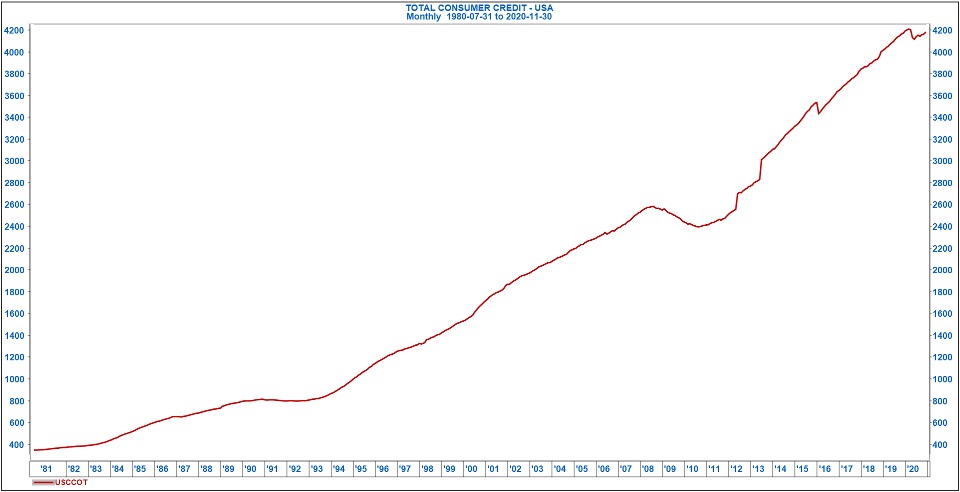

In effect, when interest rates fall from 6.5% to 1% (like they did in the early 2000’s), households borrow and spend more money, leading to economic growth and eventually higher inflation. In the next downturn, interest rates must be cut to even lower levels to have the same effect as before, especially if you consider that household indebtedness has increased over the years. The reason is that the servicing cost of debt stays the same, even at lower rates, if debt levels are higher than what they were before. See the Fed funds rate below and the declining peaks and troughs as well as consumer credit in the second chart.

US FEDERAL FUNDS RATE

Illustrating the rise of inflation

Source: Iress iGraph

TOTAL CONSUMER CREDIT – USA

Illustrating the impact of the rise of inflation

Source: Iress iGraph

2. Declining wages

When people earn less, they can spend less. Declining union memberships, the fall of communism in East Germany and the rise of China’s workforce and the world’s acceptance of China into the WTO led to a significant deflation in wages and therefore a reduction in inflation.

3. Negative interest rates do not work

Central banks possibly believe that if interest rates are negative, households may spend more money and business may invest more capital into projects. Because who wants to put money in a bank account and next year have less in the bank? But that does not play out in reality.

Household’s save to achieve certain goals, like retirement, and if interest rates are negative they will save more to achieve those goals. The signalling of negative interest rates also creates an expectation that deflation is around the corner, so why buy a new computer today if you can buy cheaper tomorrow? Businesses invest based on the demand for their product or service, not based on the cost of capital.

In retrospection, it seems that there have been many factors that explain the deflationary environment of the last 40 years. Some of these factors may have come of age or the effectiveness of policy approaches may have changed. And lastly, policies may change altogether.

More money chasing fewer goods. If money supply increases significantly (and it has gone vertical lately), deflationary forces decrease (wages, globalisation, technological advancement slows etc) and production capacity runs out of room, inflation may become a problem. Perception about inflation is also of utmost importance as it drives people’s behaviour. Jerome Powell and the Fed are doing a lot to influence expectations. In the height of the pandemic, the Fed changed its stance on inflation significantly. In effect, the Fed guided that they were targeting inflation through the cycle of 2% and would be willing to accept prolonged periods of inflation running above 2% if the preceding period was characterised by inflation well below 2% (i.e. the last 10 years). We believed the Fed was concerned about deflation and would do whatever necessary to avoid that scenario. Not even to speak about the politicians.

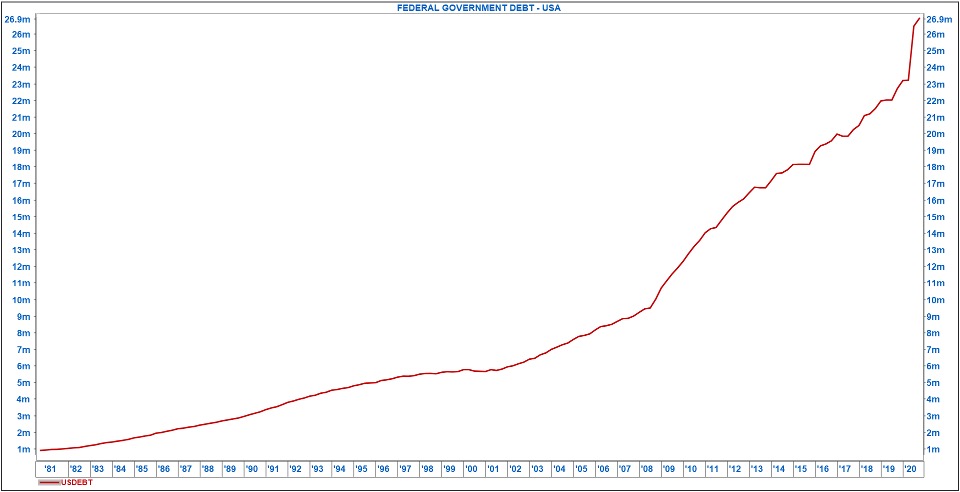

The problem with accepting higher inflation is that it is not something that can be controlled very precisely. Once the momentum gets going, how will increasing inflation be stopped in its tracks at exactly, say, 3%? The conspiracy theorist in me also thinks that higher inflation is a fine way to devalue the enormous debt burdens that have been amassed over the last 10 years or so.

Money supply – m2 – USA

Illustrating the impact of the rise of inflation

Source: Iress iGraph

Federal government debt – usa

Illustrating the impact of the rise of inflation

Source: Iress iGraph

Lastly, the stimulus cheques or helicopter money that was sent to American households was also inflationary. This was essentially cash in the back pocket of households, not the Fed buying bonds as described earlier.

Back in 2020, we believed the evidence was becoming increasingly supportive of the fact that, after 4 decades of deflation, we may have been at the dawn of a period of higher inflation and that investors should position their portfolios for this. The performance of equities relative to bonds at the time could vastly differ when compared to the results of the previous 40 years. 40 years is a long time and the psychology is such that we had only known inflation to decrease. Many market participants, including myself, have not lived through a high inflation environment. Although a difficult mindset change to make – it was probable that we may have to accept that a reversal of the declining inflation trend was on the horizon.

Fast forward to 2022

A Fed transitioning away from transitory

Powell was renominated as the Fed chair in November 2021. As we inched into 2022, it became evident that inflation was more than transitory. Inflation in January came in at 7.1%, well above the Fed target of 2% and the highest number since February 1982. The increase was largely attributed to increased energy costs, labour shortages and supply chain disruptions.

Many Americans have permanently left the workforce post the pandemic. Although the support from the Fed has come to an end, many believe they are better suited to remain at home. This, in turn, has led to businesses increasing their pay offering in an attempt to attract employees – particularly for lower income job opportunities. More disposable income for employed individuals, and the resultant increase in spending is inflationary.

Supply chain disruptions as a result of the pandemic led to suppliers not being able to meet demand as economies opened up and it picked up. Disruptions resulted in shortages across sectors. A concept known as the “bullwhip effect” exhibits how these impacts can be amplified as one moves along the supply chain. As customer demand increases, retailers order more from wholesalers, who order more from manufacturers who purchase more from suppliers. This increased demand results in suppliers selling future resources to meet current demand, thus resulting in a shortage of available items in future periods. One such example has been the shortage in chips. Chip shortages have resulted in a decline in supply of goods, and the increase in their prices as demand remains. Almost all consumer goods require semi-conductor chips – cars, home electronics, smartphones and computers to name a few. A shortage of goods demanded by consumers is inflationary.

Source: https://www.marketing91.com/bullwhip-effect/

Energy shortages, due to reduced production and limited investment into energy producing companies, have resulted in inflated prices. Energy shortages are of further concern as Russia’s production is at risk of being removed from supply. Lower supply on the back of increasing demand as economies open up is inflationary. In addition, energy is an input to all we consume and the increase in cost flows through to all goods and results in higher prices – again inflationary.

We believe the period of high inflation has just begun. It is paramount that one’s portfolio is positioned to maintain purchasing power and can withstand this period of higher prices – however long it may last.